The Lapwing is the Robin Hood of the bird world with his green coat and a feather in his cap. They often hang out with Golden Plovers and can be found on farmland, moors, and marshes throughout the UK, particularly in the lowland areas of Northern England, the Borders, and Eastern Scotland. They form large flocks in the autumn.

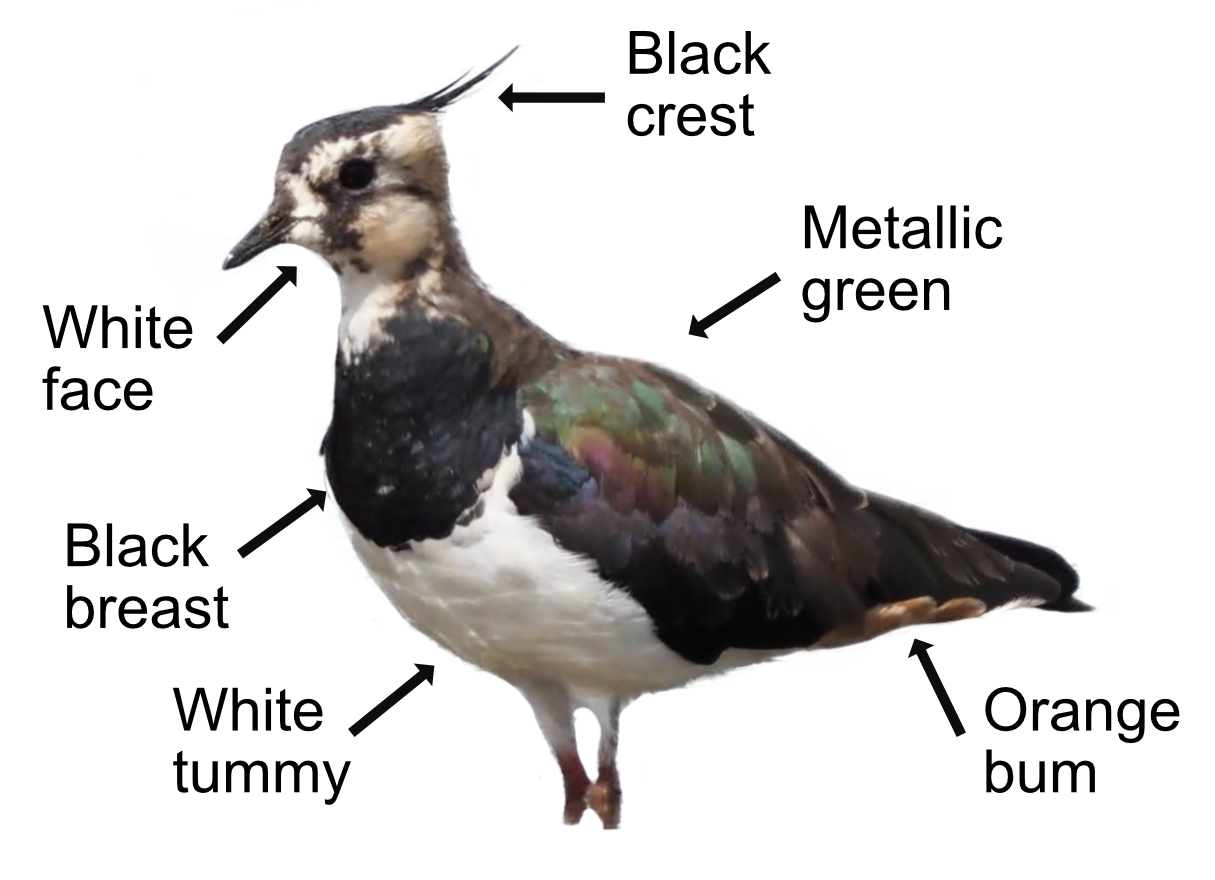

A little smaller than a Woodpigeon, the Lapwing has a dark metallic green back, a black breast, a white face, white underparts with an orangey bit under the tail, long legs, and a long wispy black crest. They have broad rounded black and white wings which make their bodies look small when flying. Their flight appears lazy with laid back wing beats. They have a distinctive "peewit" call which gives them their alternative, Peewit, name.

Lapwings eat insects like earthworms, leatherjackets, beetles, flies, moths, caterpillars, ants, spiders, and snails. Just about anything insect-ish, really. They will also eat plants.

Nesting starts in March with the male doing exciting aerial displays, tumbling about the sky over his territory in the flat open countryside. He makes several scrapes in the ground from which the female picks one and completes the nest by lining it with grasses and leaves. Her 4 eggs are beautifully camouflaged and hatch after 26 days with both birds helping with the incubation, though mum does most of it. The youngsters can feed themselves soon after hatching. If a predator comes, they stay still and hide while mum and dad do distraction flights to lure the predator away. The youngsters can fly after 35 days, becoming independent soon afterwards. From June onwards, they gather in flocks to travel around finding food .

Lapwings are highly migratory over most of their extensive range. There are about 150,000 resident in Britain with many coming over from Europe in the winter to boost numbers to 650,000. A recent decline has been linked to changes in farming with the move from spring to autumn sowing of cereal crops. Autumn sown crops are too tall by spring to make them suitable sites for Lapwings to breed. The oldest ringed Lapwing lived to be 21 years old.

Their Latin name is 'vanellus vanellus' where 'vanellus' is the Medieval Latin for the Lapwing and derives from 'vannus' a broad rounded end fan used for blowing chaff and dirt off grain. It looked like a Lapwing's wing. The English name has been attributed to the "lapping" sound the wings make in flight. The Lapwing is also called a 'green plover' as they are often seen with plovers.