The Black-throated Diver is a summer visitor to the remote lochs of northern Scotland. Like other Divers, it moves about the water with ease but is clumsy on land having its legs set so far back. It swims with its bill held straight like the Great Northern Diver. For the rest of the year, it can be found on Britain's northern coasts.

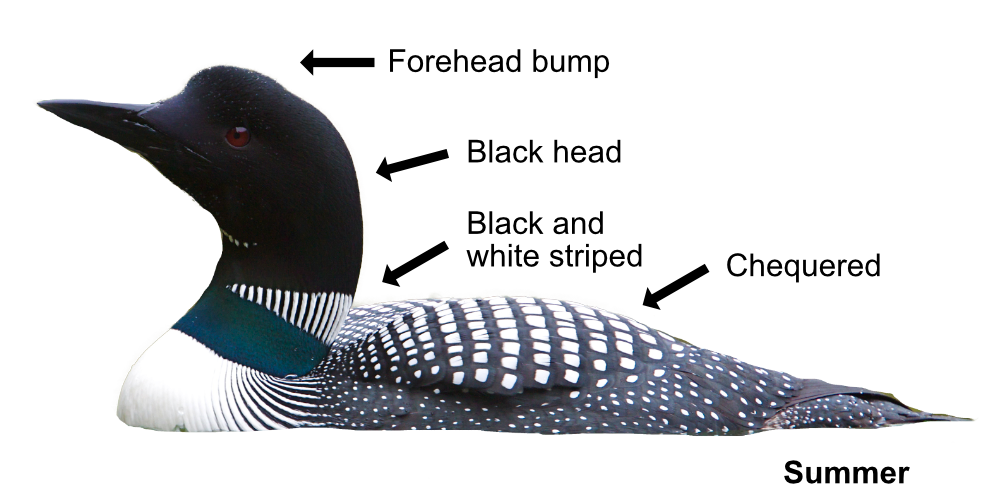

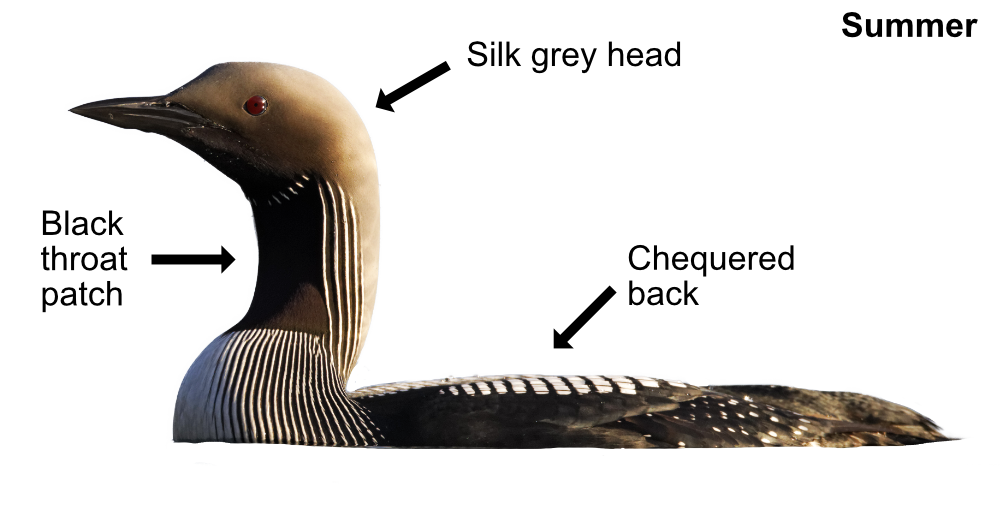

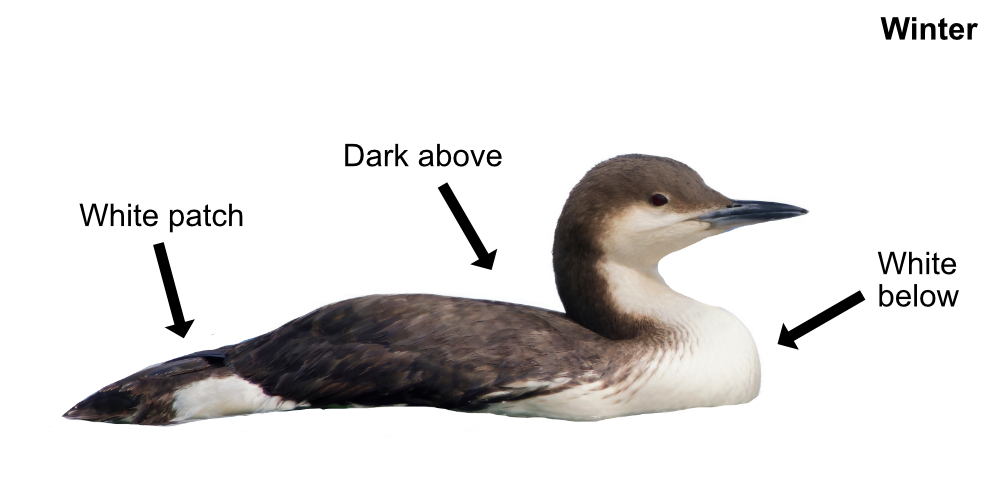

It is a large, smart, monochromatic Diver in its summer plumage. The Black-throated Diver has a distinctive black throat patch, a silky grey head and neck, a black and white chequered back, and a black dagger bill. All very Art Deco. In the winter, they turn dark grey above and white below with an obvious white oval patch on their side. They look long and thin in flight with their necks held out straight while issuing a frog-like croaking call. Other calls include a drawn-out "wup-woo-ee" wail at their breeding grounds.

Similar to other Divers, the Back-throated Diver feeds mainly on fish and can stay underwater for ages. Most Black-throated Divers search for food alone, although some small groups do gather during the winter to feed together. Just before diving, it stretches and holds its neck up at full length, then dives with a small upward jump. Their favourite food includes gobies, herrings, sprats, and sand-eels, though they will also eat insects and crabs.

Black-throated Divers pair for life and breed on large freshwater lakes from April or soon after the spring thaw. The nest is built on an island close to the water's edge. Dad constructs the nest using moss and water weeds with the help of mum (who points out where he has gone wrong). They both incubate the 2 eggs for 30 days. The youngsters leave the nest soon after hatching and are cared for by both parents, often being left alone while mum and dad go to get food. After a few weeks, the youngsters can feed themselves but mum and dad continue to provide fish until they can fly and become independent 60 days later. The youngsters won't become fully mature for 2-3 years.

Less than 200 pairs breed in Britain though numbers swell to 500 in winter with birds from northern Europe. The Black-throated Divers are easily disturbed when breeding and are also vulnerable to marine pollution. They are Amber Listed. The oldest ringed Black-throated Diver was 27 though most live for 12 years.

There Latin name is 'gavia arctica' where 'gavia' comes from the Latin for 'sea mew' and 'arctica' is Latin for 'northern' or 'Arctic'. Their English name comes from its obvious breeding throat patch. In America, it is called the 'Arctic loon'.