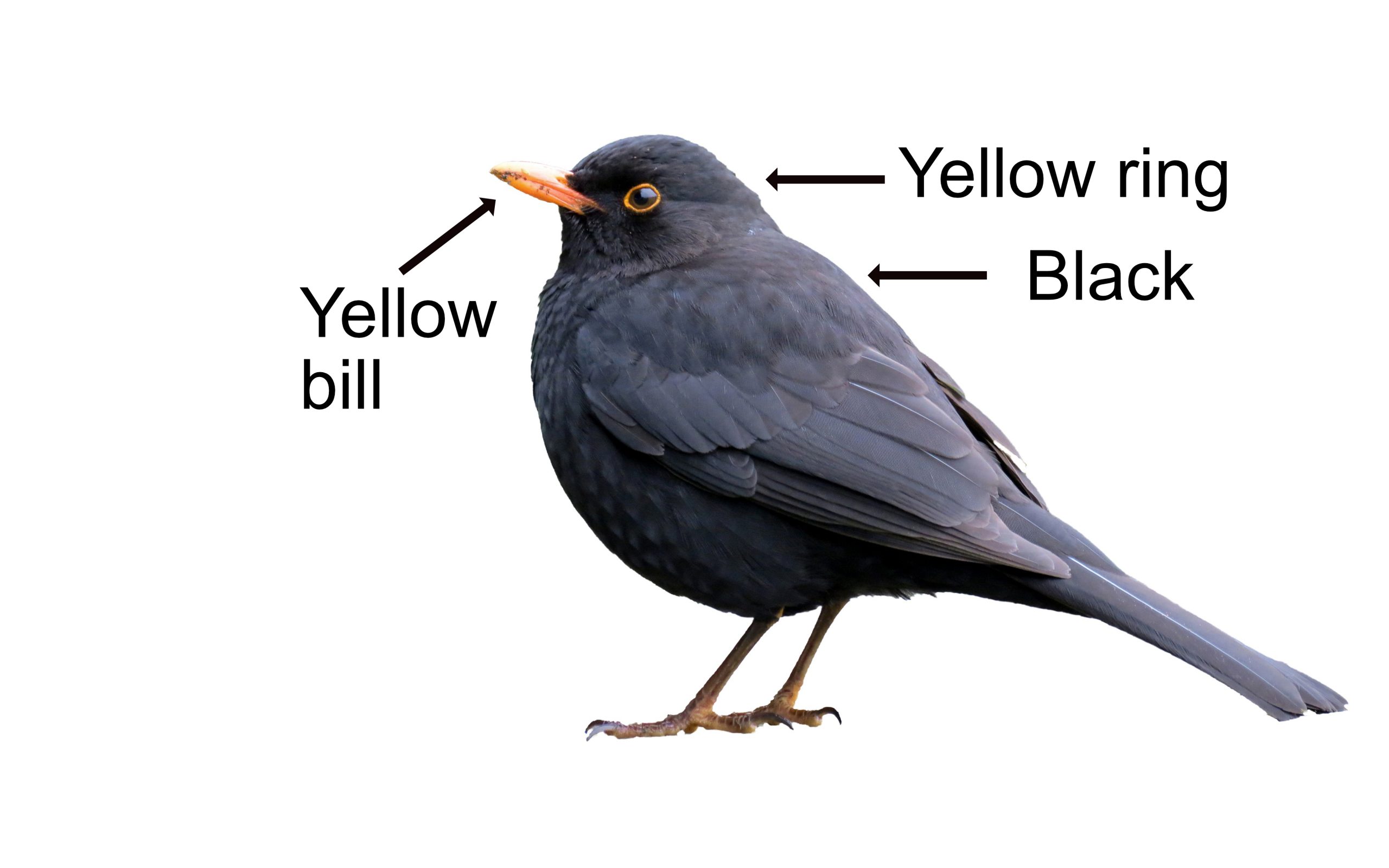

The male Blackbird is matt black with a bright yellow bill and yellow eye ring. In fact, the yellower his bill the more the girls like him. The female Blackbird is a much duller... brown! She also has a yellow beak. The male youngsters are brown, like mum, initially, so they don't get beaten up by dad confusing them for rival males.

Blackbirds make up for being boring black by having a beautiful 'flutey' song that contains many relaxed verses, like a man casually leaning against a wall and whistling away. They are the folk singers of birds. Listen carefully and you notice that the verses begin with flutey notes but end less tunefully with a squeak or chuckle. A Blackbird can have a repertoire of over 90 or more different verses. Some verses are regional, so a Yorkshire Blackbird will have a different set of folk songs to a Rutland one. They learn more verses the older they get so you can tell how old and crusty they are from the number of folk songs they can sing. Blackbirds sing louder in cities than in the countryside so they can be heard above the traffic noise - or they are just loudmouth folkies from London. Individuals have their own favourite spot to busk, so it can be easy to get to know individuals. They like a good sing, being one of the first to start up in the dawn chorus and, like the Robin, sing throughout most of the year. In stark contrast, they have a very loud and explosive alarm call which, once you know it, you can't mistake.

Blackbirds feed under or close to cover (a big bush or hedge), turning over leaves in search of their food. They like insects, snails, worms, berries (they do purple poo in the winter from eating elder berries), and fruit such as fallen apples and pears.

The female mainly builds the nest, the male being too busy showing off his upright tail stance or else out busking. The nest is made of grass, straw, and small twigs stuck together with mud. It is lined with finer grasses. Eggs can be laid as early as February. There are up to 5 eggs which hatch after 14 days. The chicks are then fed for a further 14 days. There can be as many as three broods.

Blackbirds are found just about everywhere with over 5 million birds in the British Isles and even more arriving in winter (which is typical of folk singers). Northern Blackbirds migrate south to join the southerners for a good winter folk festival. They have the Latin name ’turdus merula’ (don't laugh), ’turdus’ means 'thrush' (not poo) and ’merula’ means 'blackbird'.