A summer visitor who, of the three musketeers (Swallows, House Martins and Sand Martins), arrives first in March. The older birds arrive before the youngsters. They are most often seen in small flocks feeding over water on rivers, lakes and reservoirs as they avoid built-up areas, woods and mountains.

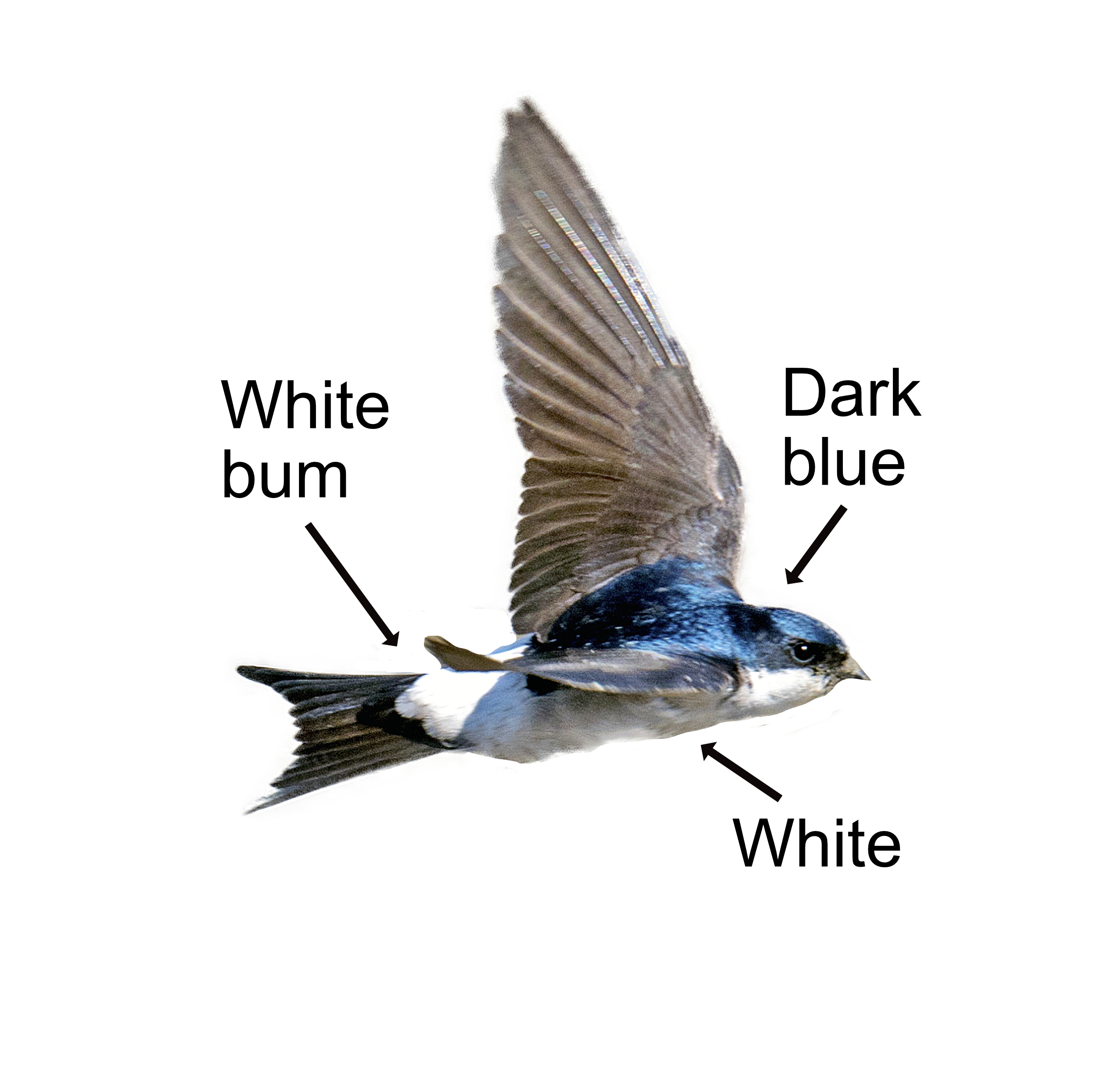

Sand Martins are smaller than Swallows. They have a brown back and white underparts with a brown breast band. Their wings are pointed and appear narrower than a House Martin's. They have a similar tail but lack the white rump. Although less graceful than a Swallow, they are still pretty good to watch. Their call is a harsh, dry, rattling "cht-cht-cht" twitter. They generally feed in gangs, flying low over water to catch insects like midges, flies and aphids.

Traditionally, Sand Martins nest in colonies in burrows on sandy cliffs close to rivers and gravel pits, though now they often use the Sand Martin hotels found on nature reserves. They are very sociable in their nesting habits; from a dozen to many hundred pairs will nest close together, depending on the available space or hotel burrow vacancies. Their nests are made at the end of tunnels which can be a few inches to three or four feet in length. Once they have dug their burrow, 4-6 eggs are laid. Both parents take turns in keeping the eggs warm, which hatch after 14 days. The youngsters can fly after 22 days and depend on mum and dad to feed them for a further week. Sand Martins will often have 2 broods and sometimes change mate if they argued too much over room service.

There are approximately 200,000 pairs in Britain over the summer, though this fluctuates from year to year as it is hard to count the fast moving blighters accurately. They depart back to Africa in August where they overwinter in the Sahel, the zone south of Sahara, where they can feed in the damp places that offer plentiful supplies of flying insects. When migrating, large flocks will gather in evening roosts on reed beds. Most Sand Martins will return to the same colony year after year. In the late 1960s, Sand Martin numbers crashed because of drought in Africa, but since then they have been slowly recovering. The oldest ringed Sand Martin lived to be 9 years old.

Their Latin name is 'riparia riparia' where 'riparia' means 'of the riverbank'. It is derived from the Latin 'ripa' for 'riverbank'. A riparian owner is someone who owns the section of a river that borders his land (including the fishing rights).