The Goosander is a relative newcomer that first bred in Britain in 1871. This handsome diving duck is a member of the sawbill family, so called because of their long, serrated bills, used for catching fish. Its long streamlined body is perfectly shaped for swimming. They are gregarious birds, forming flocks of thousands in some parts of Europe. Over winter, they are mainly seen on lakes and reservoirs.

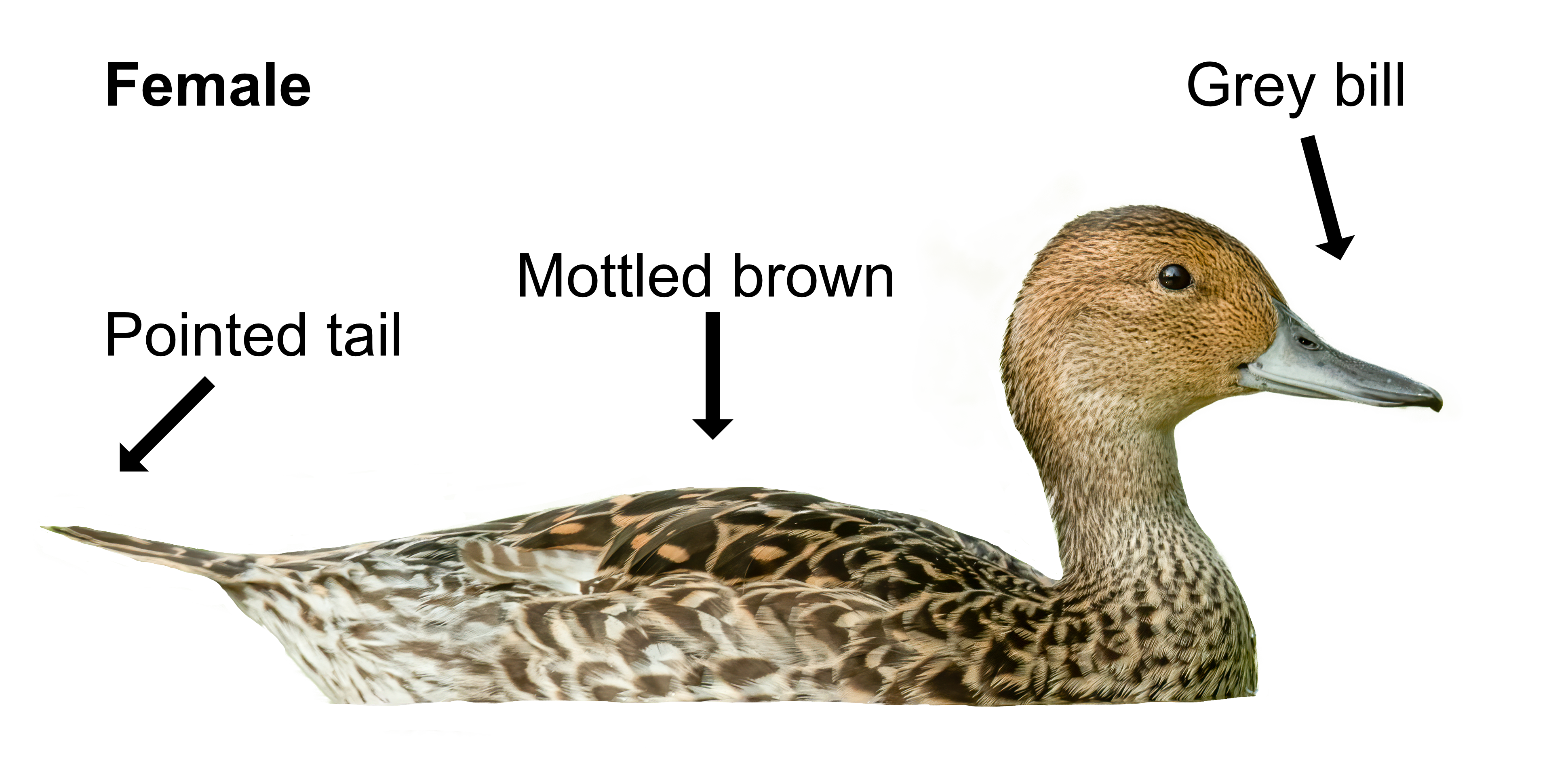

The male Goosander has a white body with a green head and black back. The female has a grey body with a reddish head, well-defined white throat and grey neck. Both have thin red hook-tipped sawbills, bright legs and dark eyes. They often fly close to the water and look long-bodied with white wing patches and black wing tips. To rise from the water, they flap along the surface for many yards. Once airborne, their flight is strong and rapid. Goosanders are mainly silent, only growling when disturbed or uttering a soft whistle during courtship.

The Goosander is mainly a freshwater bird. They swim low in the water, repeatedly dipping their heads underwater searching for food. They will feed in a group forming a semi-circle to drive the fish into shallow water where they dive to catch them, using the tooth-like serrations on their sawbill for grip. Their main food is fish like young salmon, trout and eels, though they will also eat small mammals and insects.

Goosanders breed on northern upland or hilly wooded areas close to rivers and lakes. Courting starts in winter with lots of bowing and stretching. Mum and dad then build a nest made of duck down in a hole in a tree or amongst rocks. Mum lays 8-11 eggs which hatch after 30 days and one day later, the ducklings jump from the nest, which can be as high as 18m! Once on the ground, the youngsters can feed themselves. Mum keeps an eye on them and will carry the kids on her back if there is any danger. The family may join up with other family groups for greater safety. The youngsters can finally fly after 60 days. In late summer, mum and dad are flightless while they do their 4-week moult.

About 3,500 pairs breed here, mainly in northern Britain, though they are slowly spreading south. British breeding birds stay here all year and the numbers swell to 12,000 in winter as they are joined by Goosanders from northern Europe. Their love of salmon and trout has brought them into conflict with grumpy fishermen. Overall, the Goosander is not threatened, though illegal persecution is a problem in some areas. A Goosander can live for 9 years or more.

Their Latin name is ’mergus merganser’ where ’mergus’ was used by Pliny and other Roman authors to refer to an unspecified waterbird, and ’merganser’ is a combination of ’mergus’ and ’anser’ , the Latin for ‘goose’. A goose-like waterbird. The English name Goosander is a combination of goose and ’ander’ from ’bergander’ an old name for a Shelduck. Why the obsession with a goose when it is smaller than a Shelduck and doesn’t really look like a goose is a mystery.