The Great Northern Diver is a large, robust Diver that looks a bit like a Cormorant, swimming with its body low in the water, its long periscope upright neck and its large dagger bill stuck out flat in front. It is the largest of Britain's Divers and favours shallow areas close to the shore. Another sea bird that is mainly a winter visitor, although some non-breeding birds stay off our northern coasts for the summer.

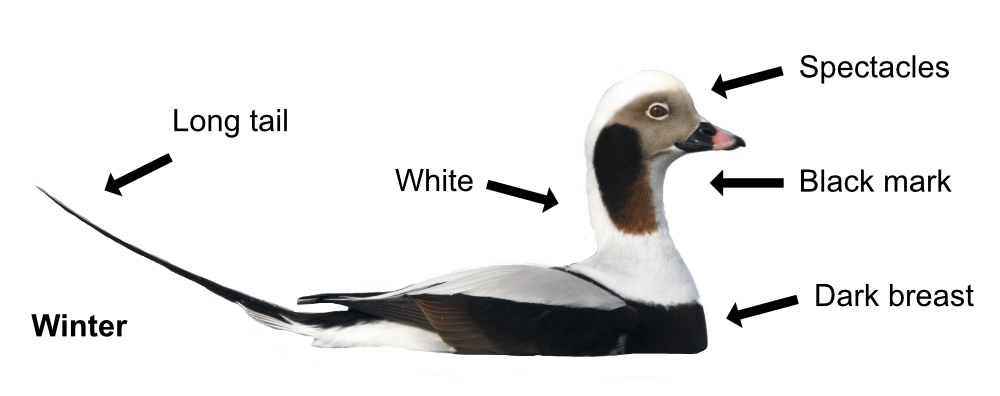

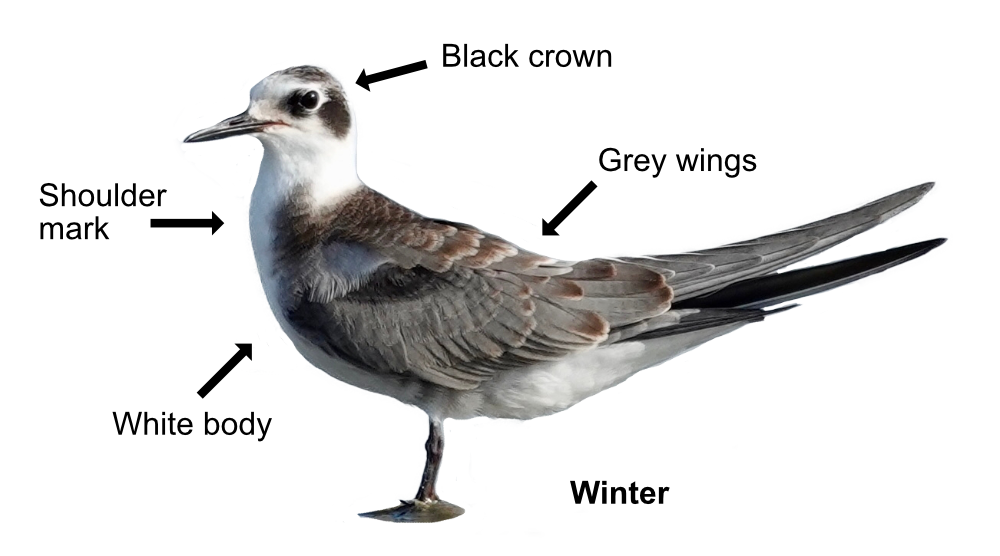

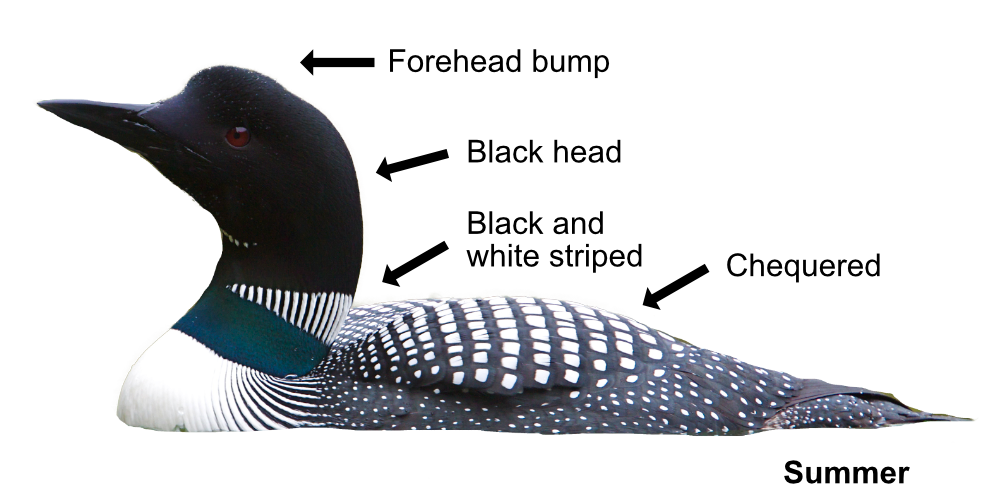

In winter, Great Northern Divers have a plain black back, neck and head, with a white throat and belly, and a darker half-collar at the base of their neck. In summer, they have a dark black head and neck with a black-and-white-striped patch on the side of the neck and a black back with a white chequered pattern. They often look as if they have a big bump on their foreheads. Youngsters are brown with white bellies. If alarmed, they will swim with only their neck and head showing above the water. Great Northern Divers fly like geese with their feet sticking out the back. Being so bulky, they have to run along the water's surface to gain enough momentum to take off. At their breeding sites, they make a spooky wailing call (which is often used on horror films) but are otherwise silent.

The Great Northern Diver is beautifully adapted and can slip underwater with barely a ripple when diving to catch fish. It normally hunts at depths of 4-10m but can go as deep as 60m. With its large webbed feet, it is an efficient, high-speed, attack submarine. It feeds mainly on fish like flounder, sea trout, herring, and haddock, though will also eat shellfish and crabs when fish are in short supply.

Great Northern Divers breed in Greenland, Iceland and North America. A few have bred in Scotland, but this is very rare. They move north to the Arctic tundra in May, where they breed on large woodland lakes or pools. Mum and dad work together to build their island or shoreline nest. Both incubate the 2 eggs which hatch after 28 days though a few days apart. Within hours of hatching, the youngsters leave the nest and swim close to mum and dad, sometimes riding on their backs. Mum and dad feed them until they can fly 75 days later, though as they grow, the youngsters will catch more and more food for themselves. The family initially stays in shallow, isolated bays where it is easier to defend the youngsters from predators such as Eagles. Mum and dad split up for winter with dad leaving first to fly south. The others soon follow. It is 2 years before the youngsters will breed themselves. Great Northern Divers are flightless while they do their late winter moult.

Great Northern Divers arrive off the Scottish coast in August and stay until May. About 4,000 spend winter here, mainly in the northwest, though they can pop up anywhere. Their chief threat, like so many seabirds, is oil pollution and getting caught in fishing nets. As not many visit Britain, they are specially protected.

Their Latin name is 'gavia immer' where 'gavia' is the Latin for an unidentified seabird or 'sea mew'. The 'immer' might be derived from the Norwegian name for the Great Northern Diver which is related to the Swedish 'emmer' for the grey or blackened ashes of a fire or it could come from the Latin 'immergo' meaning 'to immerse' as it sits so low in the water. Typically, nobody can remember. The English name is much more sensible. The Great Northern Diver comes from the north, it is big and it catches fish by diving. Simple. The Americans call it a 'loon' from its distinctive call. Fossils of similar birds have been found from the Pliocene era, so Divers have been around for a very long time.