In winter, the squat, dark Common Scoter can be seen in distant flocks bobbing on the sea or in long straggling lines flying along the coast. This highly social sea duck is mainly a winter visitor though there are about 50 breeding pairs in the north of Scotland.

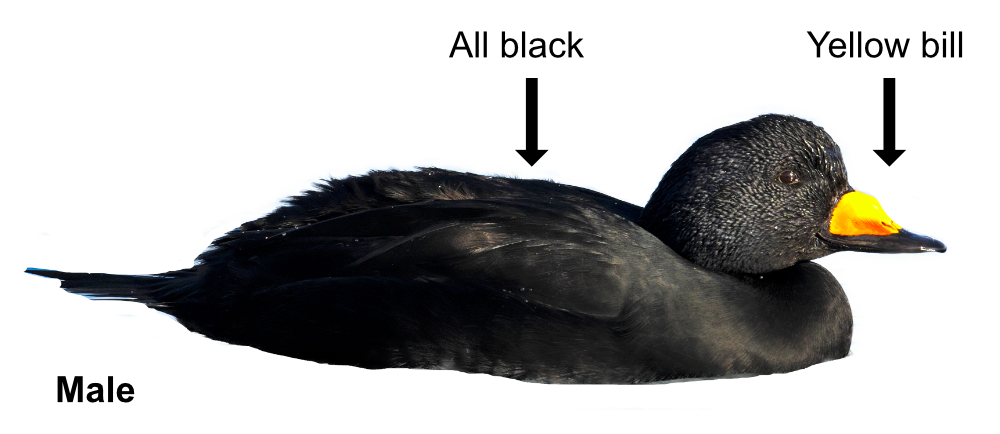

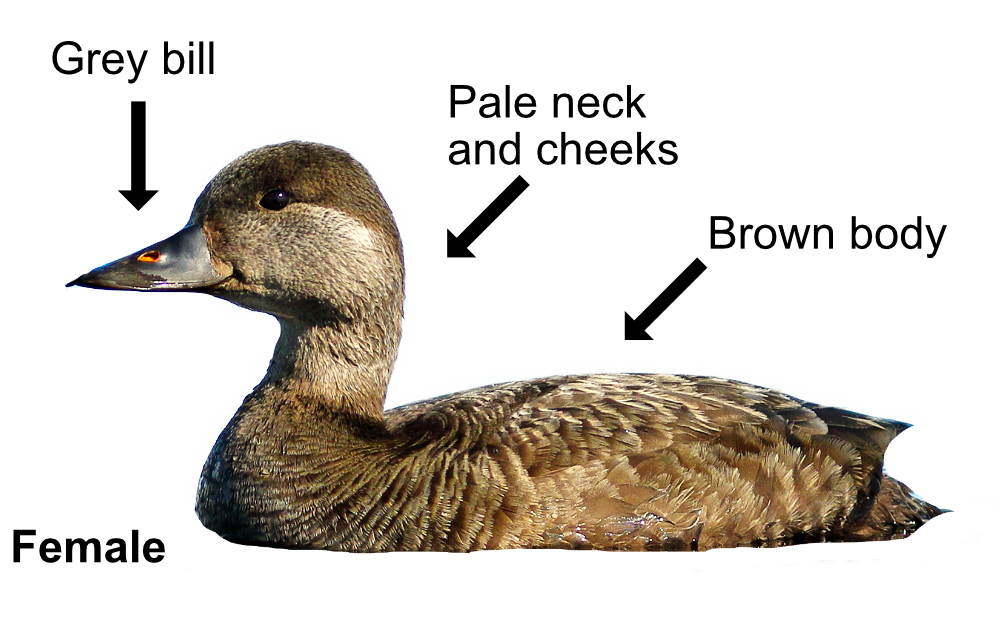

The Common Scoter is smaller than a Mallard. The male is all black with a large yellow bill that has a knob at the base and a black pointed tail. The female is brown with a grey bill, pale cheeks and pale neck. They can be distinguished from other types of Scoters by the lack of white anywhere on the male and the more extensive pale areas on the female. In flight, they appear dark and skim across the tops of the waves in long lines. The Common Scoter makes several whistle and piping calls when displaying.

Common Scoters feed on molluscs which they find by diving, using their feet to propel them downwards after a forward jump. They can dive to depths of 30 metres to hunt for their favourite blue mussels, though they will also eat cockles, clams, shellfish, crabs, insects and small fish.

Although the Common Scoter is a sea duck, it often nests amongst the vegetation of the Arctic tundra far from the sea. Courtship involves lots of head stretching and pairs form in the winter flocks before nesting begins in late May. The male defends the female at the nesting ground until the eggs are all laid and then, like so many ducks, he wanders off. The nest is a hollow lined with grass and down, usually on an island close to water. The 6-8 eggs hatch after 30 days and the youngsters can swim and feed themselves soon after hatching. They can fly and become fully independent 45 days later but won't breed themselves for 2 years. Mum and dad are flightless for 3-4 weeks while they do their moult, often at a traditional moulting ground where large flocks can gather and can stay there all winter.

The Common Scoter is specially protected as thousands have been killed by past oil spills. About 135,000 over winter around our coasts though the British breeding population has halved since the 1990s.

Their Latin name is 'melanitta nigra' where 'melanitta' is derived from the Ancient Greek 'melas' for 'black' and 'netta' for 'duck'. The 'nigra' is from the Latin 'niger' also meaning black. Like the Brent Goose, the Common Scoter was allowed by the Roman Catholic Church as a substitute for fish during the Friday Fast as it tasted fishy. The origin of the English name 'Scoter' is unclear. It might be a variant of 'scout' used as a local name for a Coot (which is black too).