The Shag (don't laugh) is hard to tell apart from a Cormorant as both can be seen on the coast, though Shags are rarely seen inland. They are mainly in the north and west of Britain, and more than half of their population is found at fewer than 10 sites, making them a Red Listed species. Like Cormorants, the Shag will often perch on rocks with outstretched wings. This pose is used for drying their wings after diving, as their feathers are only partly waterproof.

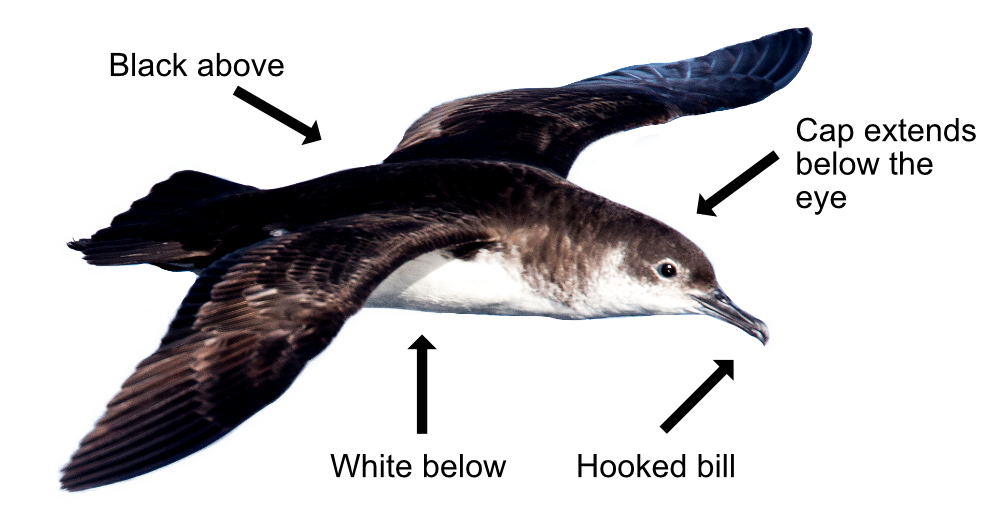

Shags are slimmer than Cormorants and have a steep forehead. They are a dark green-black with a crest when in breeding plumage and have a fine black bill with a yellow base and a small white patch on their chin. Youngsters are browner than adults, Shags are mostly silent, only making clicks and grunts at their nests. They do a gradual moult over many months, allowing them to always fly.

Shags are one of the deepest divers among the Cormorant family and can reach depths of 60m as they find their prey. They eat a wide range of fish, including herring and cod, but their favourite food is sand eels. Shags will travel many kilometres to feed. They often dive with an upward leap to help them get to the bottom.

The nest is built on rocky ledges at the bottom of a sheltered cliff site, often within a small colony. The male selects a suitable spot and both birds build the nest from a heap of seaweed and vegetation cemented together with poo (yuk!) The 1-6 eggs are laid between March and May, and hatch after 30 days. The chicks are born without down and rely totally on mum and dad for warmth. It can be up to 53 days before they can fly. They are cared for by both parents for another 50 days until finally leaving home. Shags seldom move far from their breeding area. The youngsters won't breed themselves for 3 years.

Britain has about 10% of the world's breeding Shag population with about 30,000 pairs. With their fishing from the surface of the sea, the major threat to Shags is oil spills and loss of fish stocks. Typically a Shag will live for 15 years.

Their Latin name is 'gulosus aristotelis' where 'gulosus' is from the Latin for 'glutton'. 'Aristotelis' is from the Greek philosopher Aristotle, though Shags aren't very wise. There are two other species of Shag. One is found in the Mediterranean and the other in Africa. They differ slightly in bill size and breast colour. The English name comes from its breeding crest, Shag being an old name that means 'tufted'. Another name is 'Green Cormorants' from the green sheen on their feathers.