The Ringed Plover differs from the smaller Little Ringed Plover in leg colour, head pattern, and the lack of an obvious yellow eye-ring. Most Ringed Plovers are long distant migrants, passing through here in May and September on their way between Africa and Greenland. A small British population stays here and doesn't move far, and a few others overwinter here, as Africa is a long way to go.

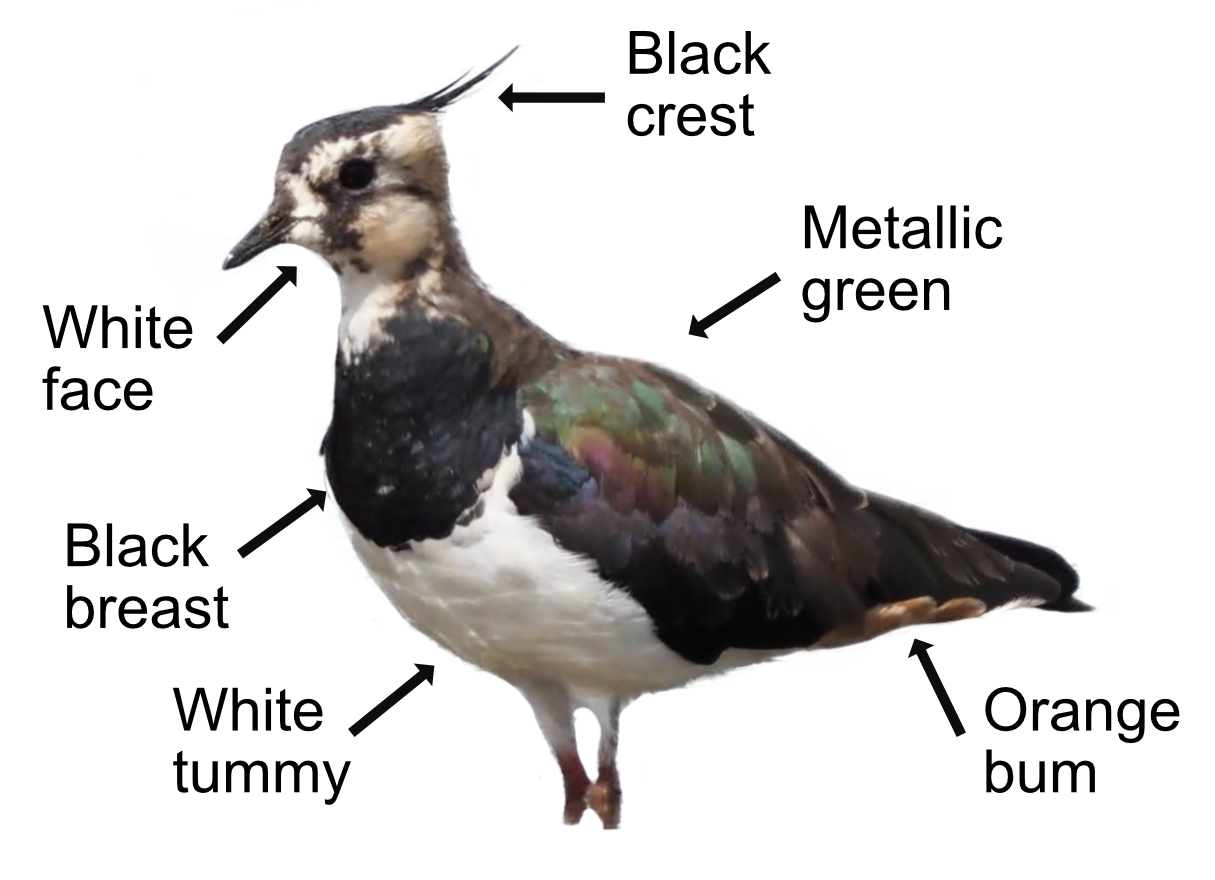

A Ringed Plover is brown, black and white and perfectly camouflaged for hiding on shingle beaches. It has a white forehead with a black band above, a black mask through its eyes, a white collar, and a black chest band. The back is brown and the underparts are white. The bill is yellow with a black tip and their legs are orange. They show a white wing bar in flight and white sides to the tail. Their flight is rapid and low and they call with a pipping "toolip". On the ground, they bob their heads when they spot something suspicious.

Ringed Plovers feed like other plovers with a short run followed by a quick tilt of their body to pick up insects or small creatures on or near the surface - a run-stop-tilt-stand action. They also use a special technique called 'foot-pattering' where they vibrate the mud with a foot to encourage worms to come to the surface. It is thought this mimics raindrops. They like to eat small insects, worms, crustaceans, shrimps, marine snails, beetles and spiders.

Most Ringed Plovers breed in the High Arctic. The British Ringed Plovers are the most southerly population and breed mainly near the coast, though recently some have moved inland to gravel pits to avoid being disturbed by noisy holiday makers. They nest on the ground amongst the stones. Nesting begins in April and the male prepares a scrape, then flies in a zigzag pattern over his territory, putting on a stiff-winged 'butterfly' display flight to attract a mate who lays 3-4 beautifully camouflaged eggs. The happy couple incubate the eggs until they hatch 23 days later. The youngsters feed themselves and can fly after 24 days, quickly becoming independent. Mum and dad will often have two or three broods.

About 5,400 pairs of Ringed Plover breed in Britain, with the largest populations being on the Scottish islands where there are fewer people. Their main threat is nest disturbance by dog walkers and holiday makers on the beach. As many as 70% now breed on nature reserves or protected sites where people are kept away. A further 36,000 Ringed Plovers overwinter here between September and April.

Their Latin name is 'charadrius hiaticula' where 'charadrius' is from the Ancient Greek 'kharadrios' for a bird found in ravines and river valleys ('kharadra' means 'ravine') and 'hiaticula' is from the Latin 'hiatus' for 'cleft' and '-cola' for 'dweller'. A double ravine dweller. I suppose ravines are stony.